I have a myriad of strange, unloved paintings shoved into various corners my studio that I’ll never actually exhibit but I can’t bring myself to throw out, either. They are all the paintings I made in front of classes I was teaching, in order to demonstrate a particular technique, to participate in whatever sadistic exercise I’d dreamed up for them to do, or just to pass the time while the students worked things out on their own. One of the many things I love about teaching art is that I get to draw and paint for the sake of modelling a process, with no requirement that the end result qualify as capital-A Art. That is a luxury, maybe even a necessity, for a professional artist with an established body of work and style and market. The pressures to produce more capital-A art can sometimes hinder my experimentation and risk. I get paid to teach, and so if teaching requires me to make quick decisions and wacky compositions, I can harness that relentless work ethic in the service of making pointless, but totally necessary, quick and dirty and weird paintings.

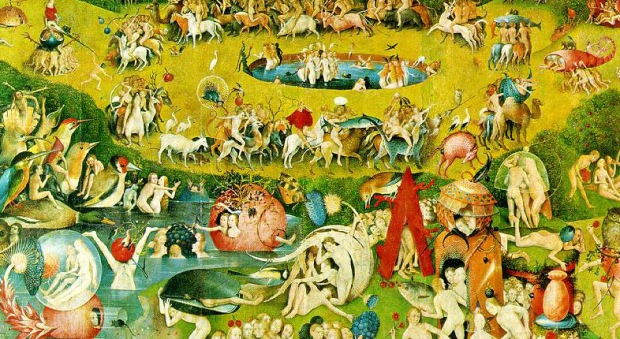

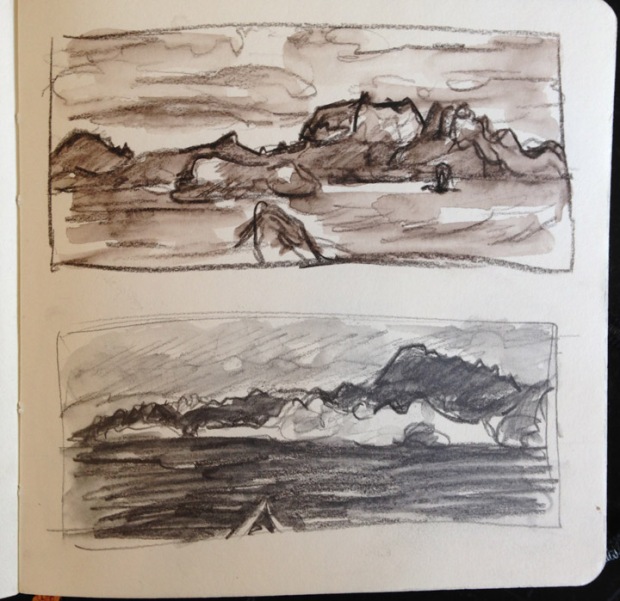

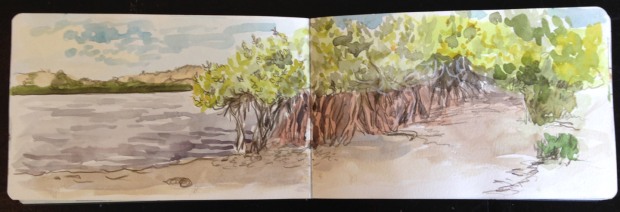

The images above and below are results of an exercise in which I require students to choose two disparate images, then divide their picture plane in half unequally, and compose the two into some kind of coherent whole. The source material for the one above was stolen from art history: Van Gogh’s boots crowding out Vermeer’s Music Lesson as if in a cinematic “wipe.” I found a common formal element in the tile floors and ran with it. Limiting my palette to the same three primaries on both sides helps tie it together as well. It is also acrylic, which I don’t own very much of, and which dries quickly and fosters immediacy.

The second one is a bit odder, possibly because it’s source material is more random. Many years ago I found a set of a couple of hundred photo cards, called the “All Purpose Photo Library,” in a thrift store. The box sat around for a long time and survived several studio moves before I finally found a purpose for it. Its original function appears to have been as some sort of elementary-school learning tool; holding up the pictures would apparently provoke meaningful discussions amongst the youngsters about communities, homes, transportation, professions, musical instruments, extension cords, plastic containers of generic cottage cheese, and the like. The set is divided with little index tabs into categories such as “food,” “inside home,” “outside home,” “land animals,” “insects” – which pretty much covers the known universe. The photos are seriously low-budget affairs dating from the late 1970’s. It looks as though on certain days a professional seamless backdrop was scored for the shoot; other days they had to make due with posing a lemon on a paper Chinet plate. In other words they are pretty much perfect, just have the students blindly choose two of them and then make a painting out of it. Ego investment, overthinking, preconceived notions about high versus low – poof! GONE!

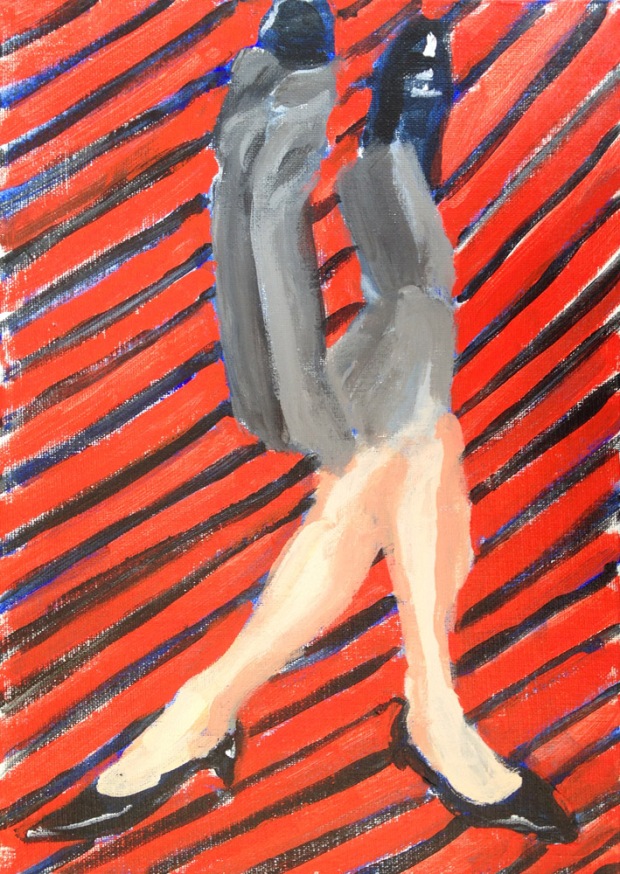

In a related exercise, I had everyone bring in a bunch of magazines, from which we made collages, which then became the basis for paintings. I’ve since lost the collage for this one, but I appear to have made a handy unisex bathroom sign should the need for one arise.

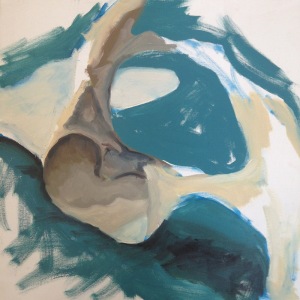

I also have a fondness for simple still lives, which I would never take the time for in “real life”. But it’s really great to just PAINT sometimes, not worrying about the “Art” part of it; I remember why I do it in the first place. These are from “Color Boot Camp” demonstrations of limited palettes. The first was from a Saturday afternoon quick demo at the Bellevue Art Museum years ago. Space and time were both limited, so I grabbed a bone from my bone collection and four tubes of paint, showed up, and painted it in front of a group of random strangers, making up the blue background on the spot.

Here a lime and a paper bag were the props on hand. (It’s harder than you’d think to match the color of a paper bag.)

Here a lime and a paper bag were the props on hand. (It’s harder than you’d think to match the color of a paper bag.)

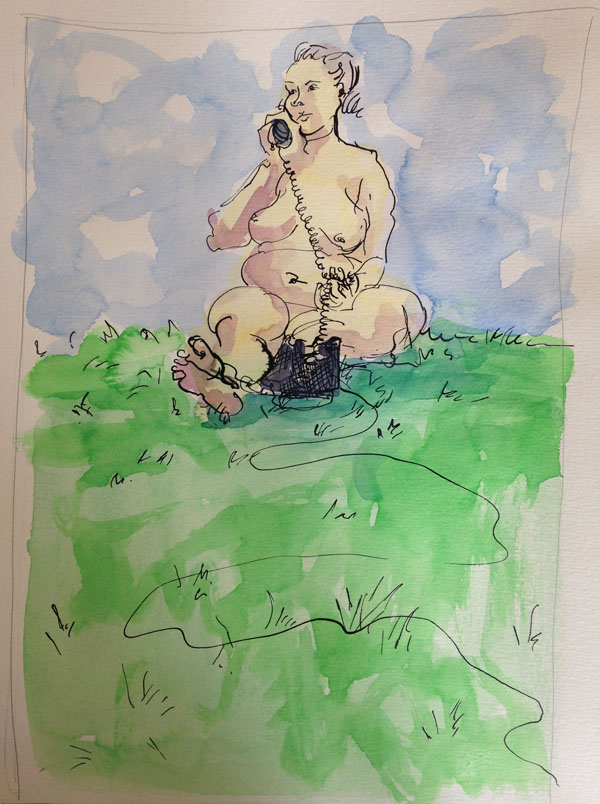

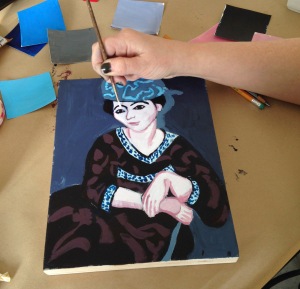

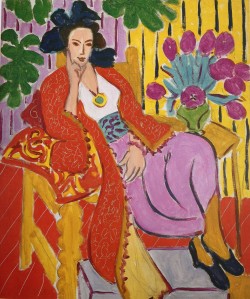

My favorite demonstration paintings, however, are the ones that end up reflecting and distilling the true concerns of my real work, anyway. I paint people all the time – slowly and from photographic sources and in great detail, sometimes hiring a model for a missing part of the pose, and working carefully around the edges of the fabrics I paint on – but when I’m teaching a figure painting class I can work loosely and quickly, making fast decisions about color and composition and not worrying about the edges.

I borrowed a gumball machine from one of my studio neighbors, hung up a striped sheet, added some furniture, a mirror, and a telephone, hired Ruth, and asked my class to make a narrative out of it. Or not.

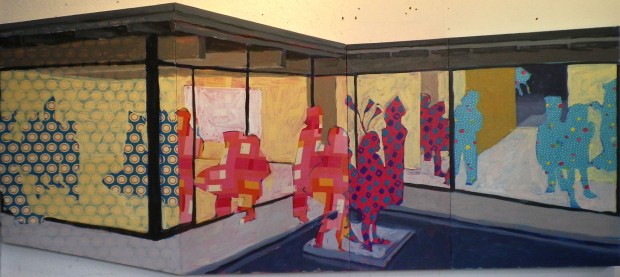

At Pratt many years ago I taught a class called Pattern, Rhythm, and Pictorial Space. This painting I did of Megan in their sun-filled classroom – a former Wonder Bread factory outlet store – is one I like to pull out and look at for inspiration sometimes.

Most of the fabrics I used in the set-up have since disappeared into paintings.

Most of the fabrics I used in the set-up have since disappeared into paintings.

In the same class, I organized a “still-life potluck”, in which everyone brought patterned objects from home, all of which I arranged into a cacophonous still life. Always thrifty about the materials for these throwaway paintings (which never seem to get thrown away), I painted this on an old piece of mdf that was once part of a floor in a play at ACT Theatre.